When Urbanists say “urban”

What do "urban" and "suburban" actually mean?

On my last post, I got a comment asking “Why should a suburban area with good access to public transportation and pathways to get into the towns and cities not thrive?” My initial reaction was that this was a category error — if a place has good public transportation and pathways into towns and cities, by definition it is not a suburban place.

There are several problems with my initial reaction.

First, the comment represented a perfectly normal and understandable confusion. “Urban” and “suburban” are common words with many meanings and deep, divisive connotations. When I said suburban pattern, meaning something specific about land use and transportation, I think the commenter very reasonably interpreted that to mean something like “smaller cities outside a larger city.” (And she was correct, there’s no reason that smaller cities outside of a larger cities shouldn’t thrive.)

The deeper problem with my reaction is that “Urbanists” use these labels “urban” and “suburban” differently than most people. In some ways we’re being more specific and technical than the colloquial usage, but at the same time, even urbanists don’t have a precise, shared definition of these words. Our peculiar vocabulary is signaling shared values more than it is forging shared understanding.

Today I want to illustrate the confusion around these terms, sharing how I think about what “urban” means via some examples that I think many people would find surprising or highly debatable.

But before I start, I want to emphasize: I don’t think it’s realistic to expect the majority of people to re-learn what these words mean. It’s probably not even feasible to get the majority of urbanists to standardize on my definition of “urban.” My goal today is just to illustrate the dilemma. I’ll close with a brief thought on what we might do instead, and expand on that in a follow-up post.

Disclaimer given, let’s dig in.

Is it about being a satellite or a center city?

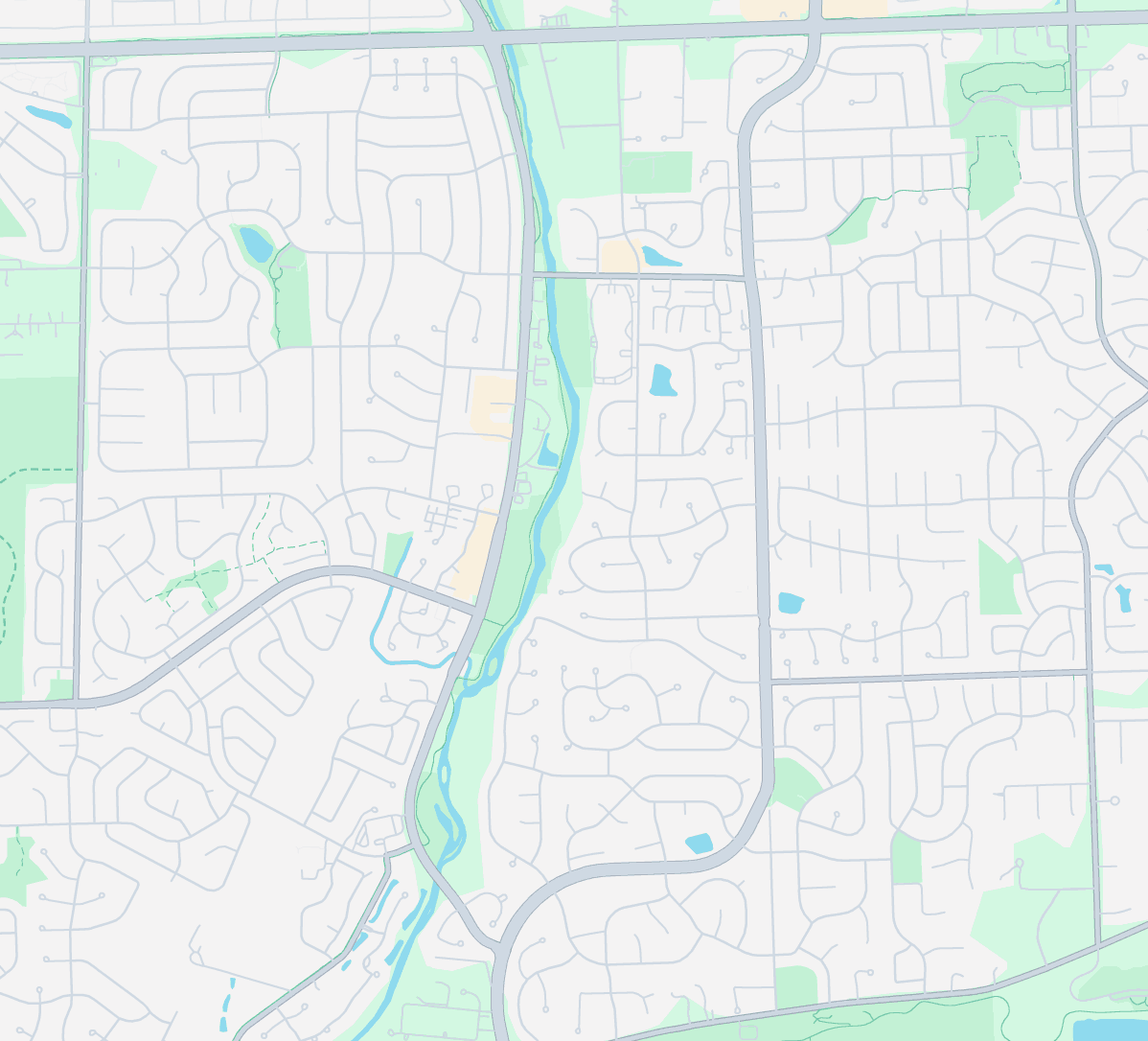

Here are two satellite towns just outside a larger parent city. Are these suburban?

Round Rock, Texas is the next town north of Austin. It’s deeply, quintessentially suburban.

Somerville, Massachusetts is north of Boston, but it’s deeply urban.

The commute patterns and economic positions of cities relative to each other don’t determine the “urban” or “suburban” nature of the place.

Is it about the level of development?

If urban/suburban isn’t about the commute patterns, perhaps it’s about higher or lower levels of development.

This photo is a classic residential subdivision in Naperville, Illinois

This one is a dense commercial zone in Irvine, California.

Both places are deeply suburban in pattern; if you look at a map it’s hard to tell which is which.

Overall these cities are very spread out and not walkable, even though they may have pockets of walkability. In particular, Naperville has a very nice, and I would say very urban downtown.

Is it about walkability?

Let’s talk about walkability. Here are two pedestrian pathways. The first is in a suburban context, and the second is in an urban context. Obvious, right?

Actually, this is the same path: The Woodlands Waterway, in The Woodlands, Texas. Despite the tall buildings, all of the Woodlands is deeply suburban. While the pathway is a great recreational amenity, it’s not much practical use.

What about these two?

These are both photos of the San Antonio Riverwalk. The level of development alongside the river changes dramatically from the first photo north of downtown to the second photo in the heart of the city, but both are surrounded by and connected to an urban context.

So, walkability is necessary but not sufficient, the surrounding context is critical.

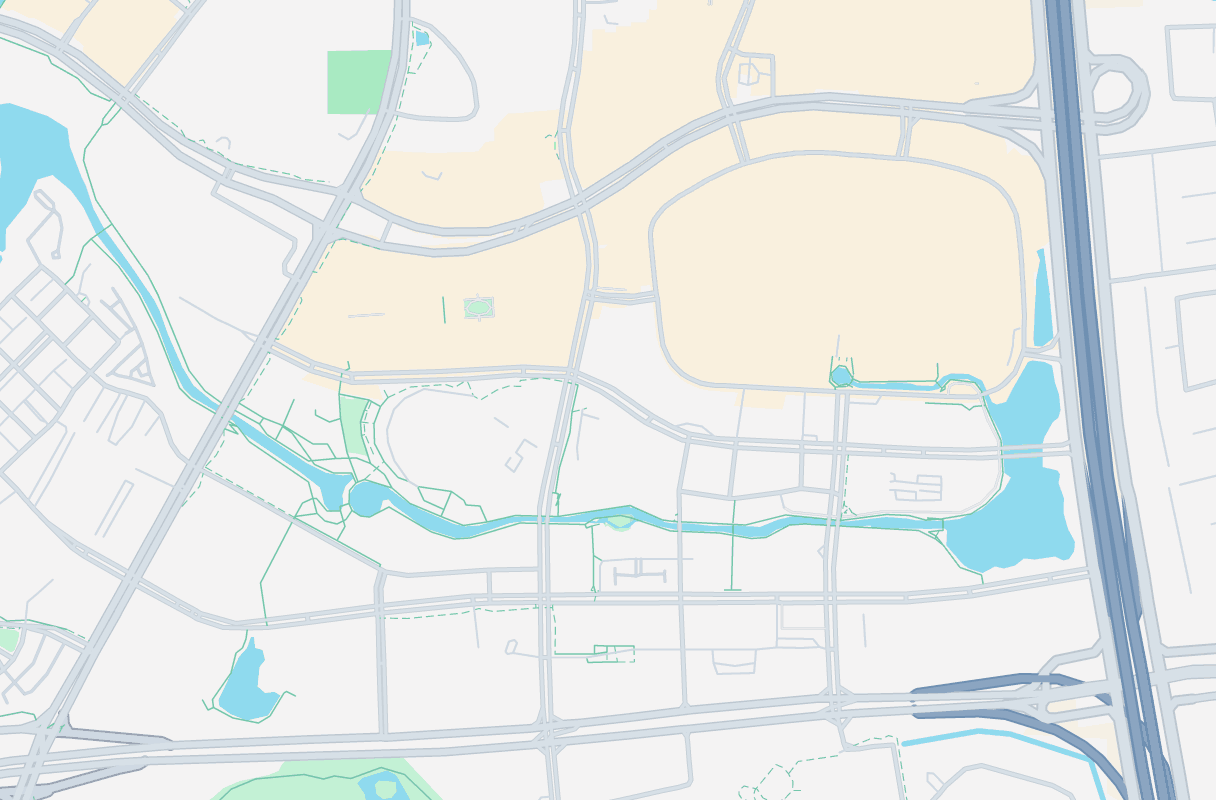

Is it about the street grid?

After the last example it seems like the key is the street pattern, so let’s take a closer look at that. Consider these street maps and tell me which major cities these are:

Hard to tell? These are, in order:

Peabody, Kansas. Population 937

Eugene, Oregon. Population 176,654

Chicago, Illinois. Population 2,746,388

Before you go thinking “ah, he got me with Peabody,” I would argue all three are urban places! Why just look at lovely Peabody’s downtown.

It’s tangential to this post, but I love how these three places beautifully demonstrate the magnificent American street grid happily scaling to support a city of any size. We should default to grids again!

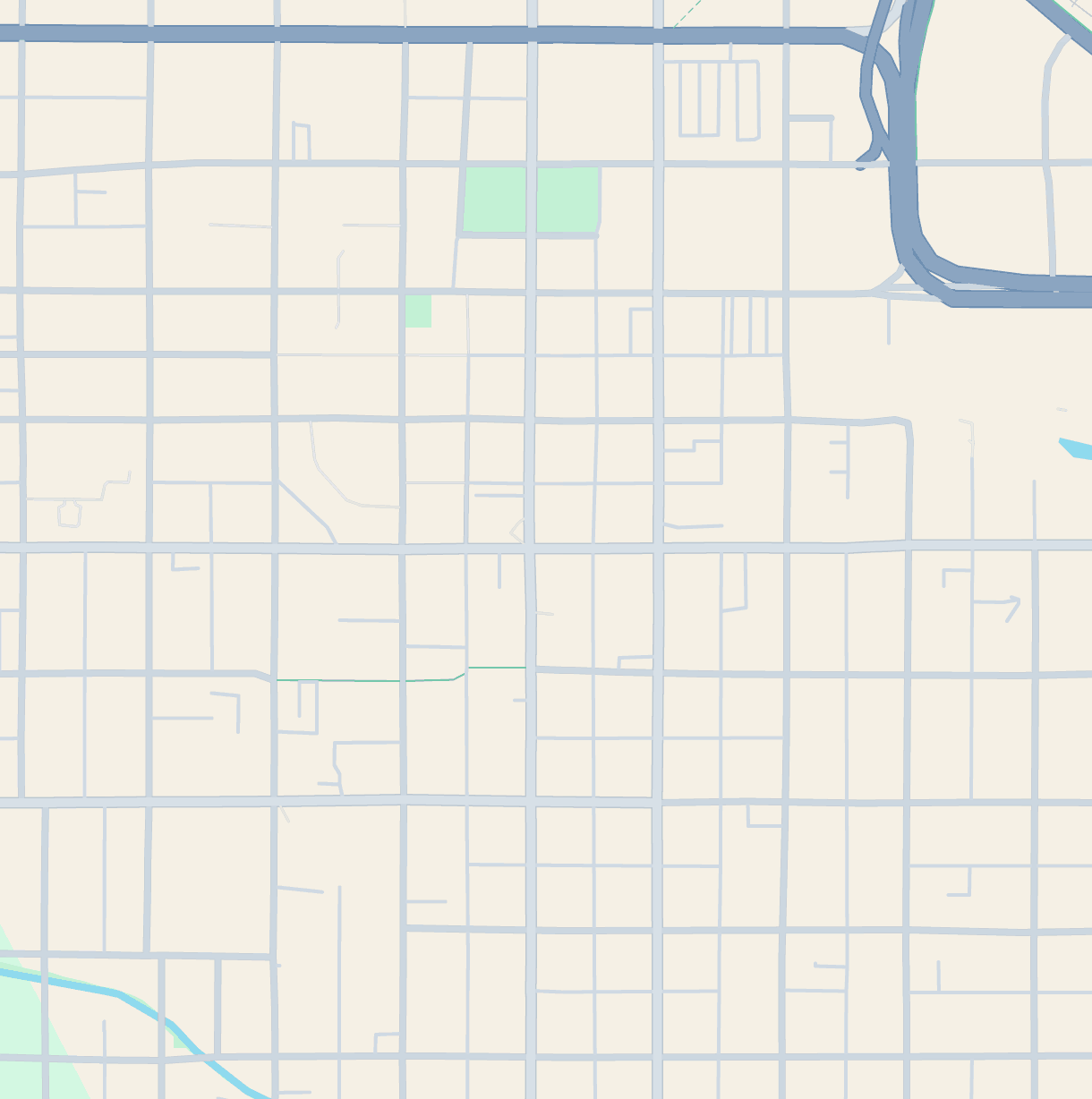

So the grid is the answer, right?

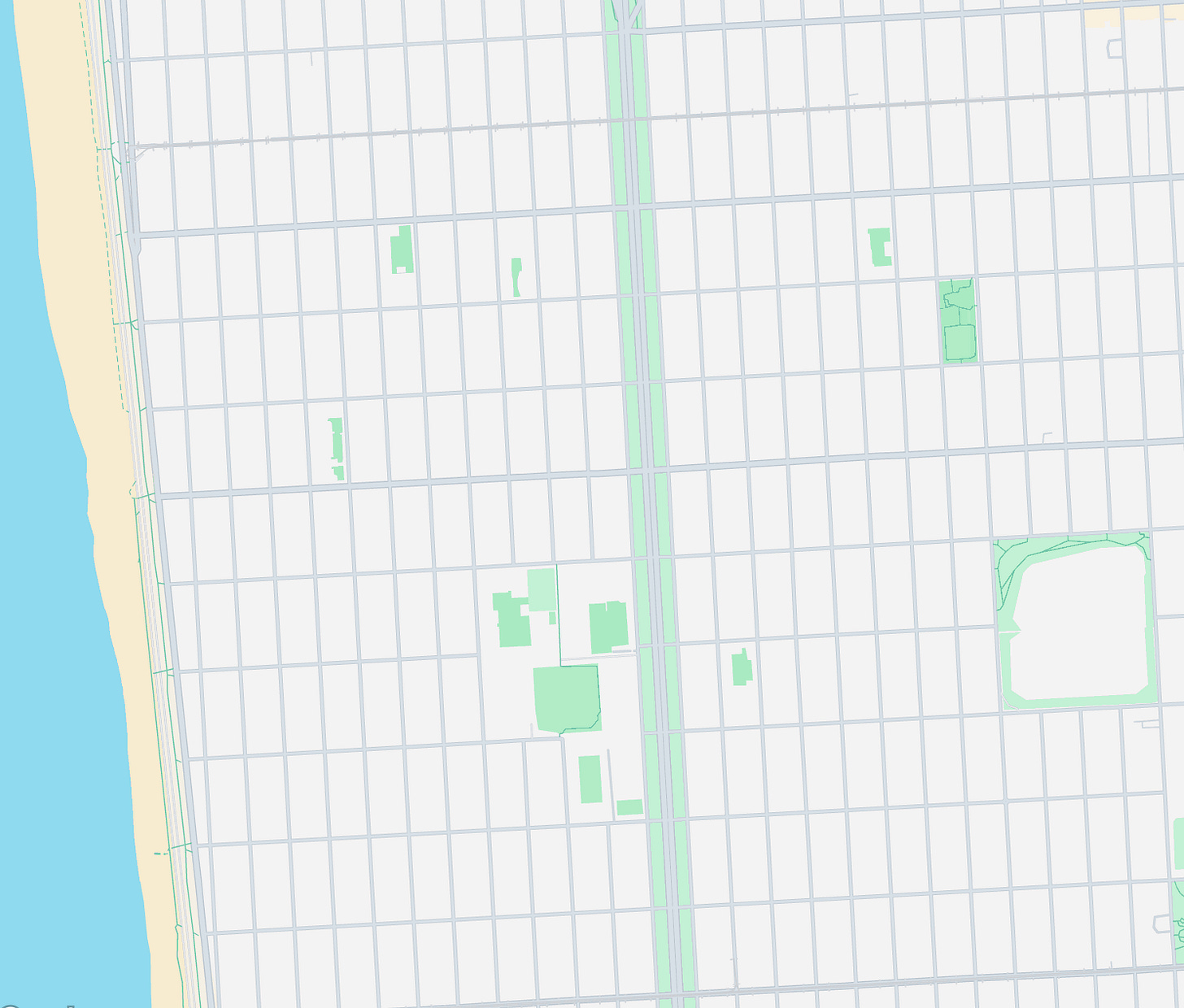

Unfortunately, no. Consider the Outer Sunset of San Francisco.

Gridded, dense by American standards, but utterly suburban.

In this place of only houses there isn’t enough mix of land use, you need a car, or at least a bike, to make life practical.

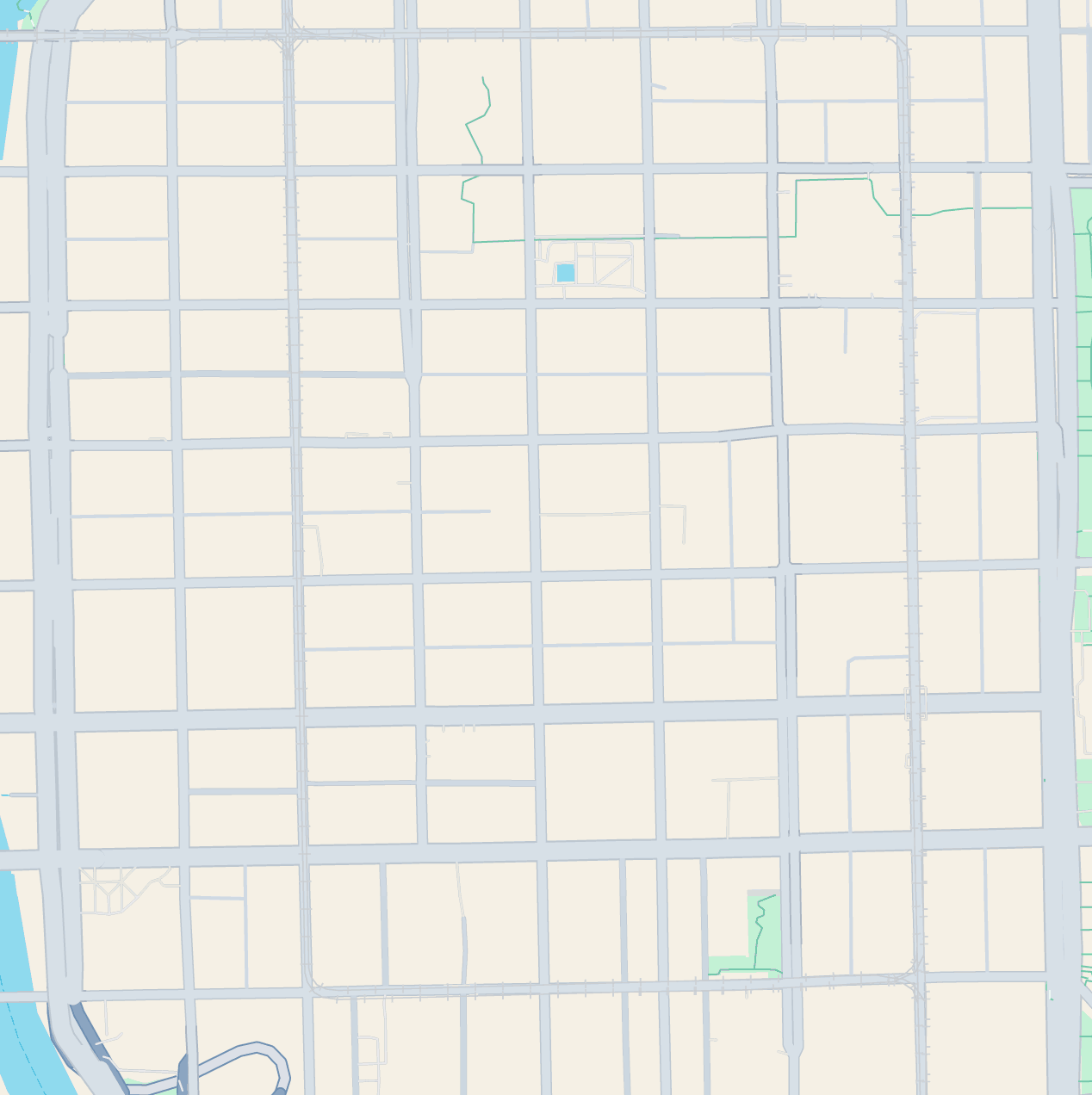

The New Urbanism

There’s one more point before we move on. The traditional neighborhood developments of the New Urbanism check every box. Walkable, connected streets, mixed uses, beautiful design. I mean, just look at this:

I’m sorry to say this is not urban.

I’m picking specifically on the crown jewel, Rosemary Beach, but nearly every greenfield project of the New Urbanism fails to be “urban” in the same two ways:

They’re not connected to a living city fabric — ie they’re islands that can’t grow! Look at the map of Rosemary Beach, and see how it’s walled off from the surrounding context, without connections to adjacent development. There won’t ever be a new part of Rosemary Beach.

Just as important, these developments are frozen in time with highly restrictive zoning and covenants that would make your nosy neighbor blush.

These places aren’t urban. They’re theme parks.

They are beautiful, wonderful theme parks, and I love them more than I love Disneyland, for showing us that we can still build nice things, and proving how hungry the market is for real cities to be born and grow again.

But these aren’t cities, and they aren’t urban. They’re islands, built to a finished state, and deeply, fundamentally, suburban.

So what is “urban”?

Now that I’ve offended everyone who could possibly read this post, let me finally offer my definition of urban:

Urban means a living community (not controlled by a single party, ungated, allowed to grow and change), where it’s safe and comfortable for humans of all ages to live independently (able to reach daily activities on foot).

But after all that work to explain my definition of urban, I’m going to suggest we not use it very much.

Unfortunately, for many people “suburban” and “urban” mean roughly “good” and “bad.” Which one you think is “good” and “bad” have a lot to do with your age, where you live, and your personal politics. But because the majority of Americans live in the suburbs, more people think of “urban” as “bad” and “suburban” as “good.”1

As advocates, if we start our conversations by taking about how to make places more urban, or promote better urbanism, we lose a lot of the audience right out of the gate. And even in “urbanist” spaces like this newsletter, where I’m writing specifically for high-context advocates and not the broad public, we have a high risk of talking past each other, as the images in our heads don’t quite line up.2

Rather than relying on broad, connotation-laden terms, I think we should probably try to shift to more specific labels when we can; especially when describing problems and solutions in cities and towns. I think we could focus more on the key characteristics that most impact how places work, and specifically how well they function for non-augmented humans. And if we focused a bit more on those specific characteristics, we might understand each other better, and might even be more persuasive.

In my next post I’ll share what I think a few of those labels might be.

Addison Del Mastro has written many thoughtful pieces grappling with how we think about cities and what urbanism means, and in a delightful coincidence he published another one today. If you want to wrestle with this more, I highly recommend his newsletter!

As an ironic footnote to all of this, I realize that my newsletter itself violates my recommendation. When I started writing I wanted to talk about what comes next after the suburbs, hence “post-suburban,” but a year later I feel that phrase still hasn’t clicked. I’m actively considering changing the name to something else. Suggestions are welcome!

"So, walkability is necessary but not sufficient, the surrounding context is critical."

Well, another way to think of it is that context is part of "walkability" for urban purposes. We don't mean just a safe foot path for exercise and nature appreciation, fine as those are; urban walkability requires functional destinations.

Excellent article. Anytime a subject starts to take on political salience on any level, certain terms within just become meaningless Rorschach tests. Suburban and Urban have likely fallen into that category. I think to really draw a proper picture in folks heads, particularly conservatives who tend to be predisposed against anything 'urban', we need to speak fondly of the American 'Main Street' and 'traditional cities' like Paris, Rome, pre-war Chicago and NYC, etc., and talk about how 'technocratic' post-WWII land use and building regulations and practices (setbacks, single-use limits, parking lot reqs, huge streets, etc.) have made it illegal to build in the same style of the folks who built the greatest cities of Western Civilization (conservatives love this stuff).

This is likely the best way to apply the technique of 'Moral Reframing' to urbanism when talking to conservatives; it's the same arguments, but appealing to different values and using their language. You already have the true believers; why preach to the choir when you can secure Converts?

Though, keeping in mind that Substack's model greatly rewards writing for one's existing audience, the best approach is likely for non-conservatives and more urbanism-fluent audiences is likely to just get hyper-specific and use more pictures, while weaving in some occasional moral reframing.