How to make a great street

A visual guide

In 2024, about 53 Million of Americans traveled abroad, largely to visit places that look like this:

This constitutes a vacation from living in places that look like this:

For the people who live nearby these are both “ordinary streets,” but as you can see the experience of being in these two places is radically different. The first is an exciting, lively environment that makes you want to wander around and explore. The second is a public utility you drive through because you’re going somewhere, not a place you’d want to stop and hang out.

This difference is so stark because they’re actually two different things. The photo from Amsterdam is a Street: a public space that connects individual properties and provides human access and circulation through a neighborhood. By contrast, a Road is a dedicated path for moving vehicles from point A to point B as quickly and safely as possible. And, unfortunately, the photo from Aurora is a Stroad, a dangerous hybrid that tries to combine high-speed traffic with local access and does a bad job at both. (For a deeper dive see Streets and Roads).

The bare minimum requirement for a street is that it’s a publicly accessible space that usefully connects multiple properties. An example would be a residential street with a sidewalk. If people can practically use it for walking their dogs and visiting their neighbors, that’s a street.

If people can’t walk around and experience the space outside a vehicle, either because of the excessive distance between points or because there’s no safe place for pedestrians, then it’s not a street.

What is a Great Street?

A great street is a public space that’s fun to explore.

Great streets attract people.

They create convergence points, a virtuous cycle of investment and wealth creation.

A Great street a place where you’d do more than just visit a home or a business, you’d want to hang out.

As a visitor, a great street makes you think fondly about moving to the neighborhood.

As a resident, it makes you feel connected to, and proud of, the place you live.

Why should Great Streets be a priority?

North America has plenty of historic streets, some of which are well-preserved and remain vibrant to this day.

But in our mid-century excitement over the automobile, we lost our cultural memory of what streets are, and how to make them great. So in most of our places that look like this…

…we did things like this:

Notice that in the second photo, we have both a low-rise strip center on the left, and a mid-century high-rise apartment building in the background. You can see how this is discontinuous from the historic Main Street environment it replaced. It’s worth noting: those developments mark the last time it was easy for developers to replace small old buildings with larger ones. That lost ability to build great streets contributed to the general anti-development shift in our culture1.

For pro-housing advocates in supply-constrained cities: if we want to shift the culture around adding housing, and to build momentum and support for infill and abundant incremental development, that development has to make neighborhoods nicer, not just denser. That means treating streets as important public spaces, and ensuring that buildings connect to them well.

Creating the right conditions

Once we’ve set our minds to making great streets, we face a dilemma. Actually, cities can only create good streets. Truly great streets have to emerge organically, but they can only do so where the conditions are right.

In City Comforts, David Sucher describes it this way:

Caution to planners:

Creating community — which is what all this boils down to — is a worthy goal. But it is a goal largely beyond the reach of government.

Community evolves from individual conversations. … Interesting public spaces provide only a framework, with the daily details supplied by aware entrepreneurs who recognize what is working and what is not, and act immediately.

So our actual goal is to create a good street, with the right conditions for a great street to emerge. To do that, we’re going to have to solve three problems:

What to do with the conduits, especially the travel lanes for cars

What to do with the public interface, i.e. the walkway and any public space around it

What to do with the private interface, i.e. the way the private property attaches to the street

In the rest of this essay I’ll describe how we can solve each of these, listing the solutions in order of importance. This is a longer post than usual, so I’ll also include a short recap at the end.

The parts of a street

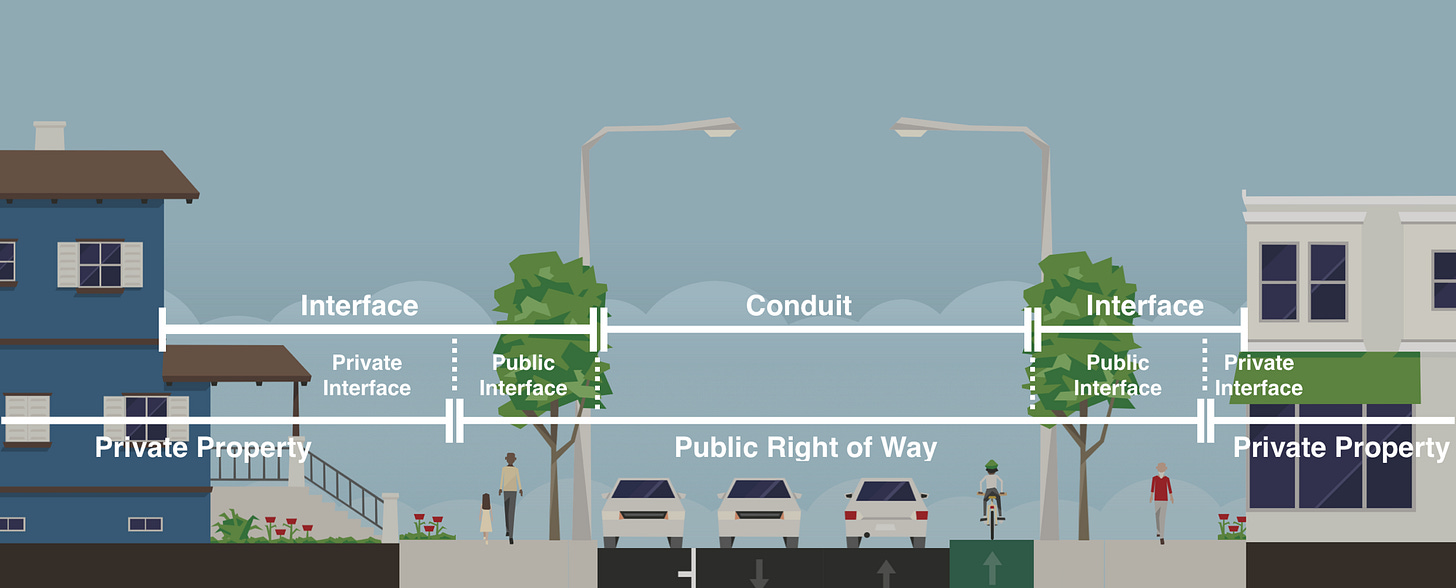

One last thing: before we talk about how to make a great street, we need to understand its component parts.

Most streets contain multiple conduits, the main one being the dedicated lanes for cars down the middle of the street. Other conduits include utility lines (power, telecom, sewer, water), or possibly bike or bus lanes.

Outside the travel lanes we have the Interface, the connection between the public and private space. Public property (specifically the Right of Way, or ROW) typically extends well past the curb; it often includes a planter strip and ends at the outside edge of a sidewalk.2 Private property abuts the ROW, but the front edge is semi-public in character; picture front yards, porches, patios, storefronts, etc. (For a deeper dive, see The Elements of a City)

Handling the Conduits

The first requirement of a good street is that it be safe, which mostly means safe from automobile traffic.3 To do that, we design the travel lanes such that people will naturally drive slowly — in practice 20mph or less.4

Narrow lanes

The biggest factor in driving speed is the width of the travel lane, so to limit speed we keep travel lanes narrow. From there we can add curb extensions like gateways and pinchpoints, or horizontal deflections, called chicanes, that make drivers turn slightly.

On-street parking also helpful, since it has the effect of narrowing the travel lanes, providing a physical barrier between pedestrians and cars in motion, and providing convenient access for people who drive to the street.

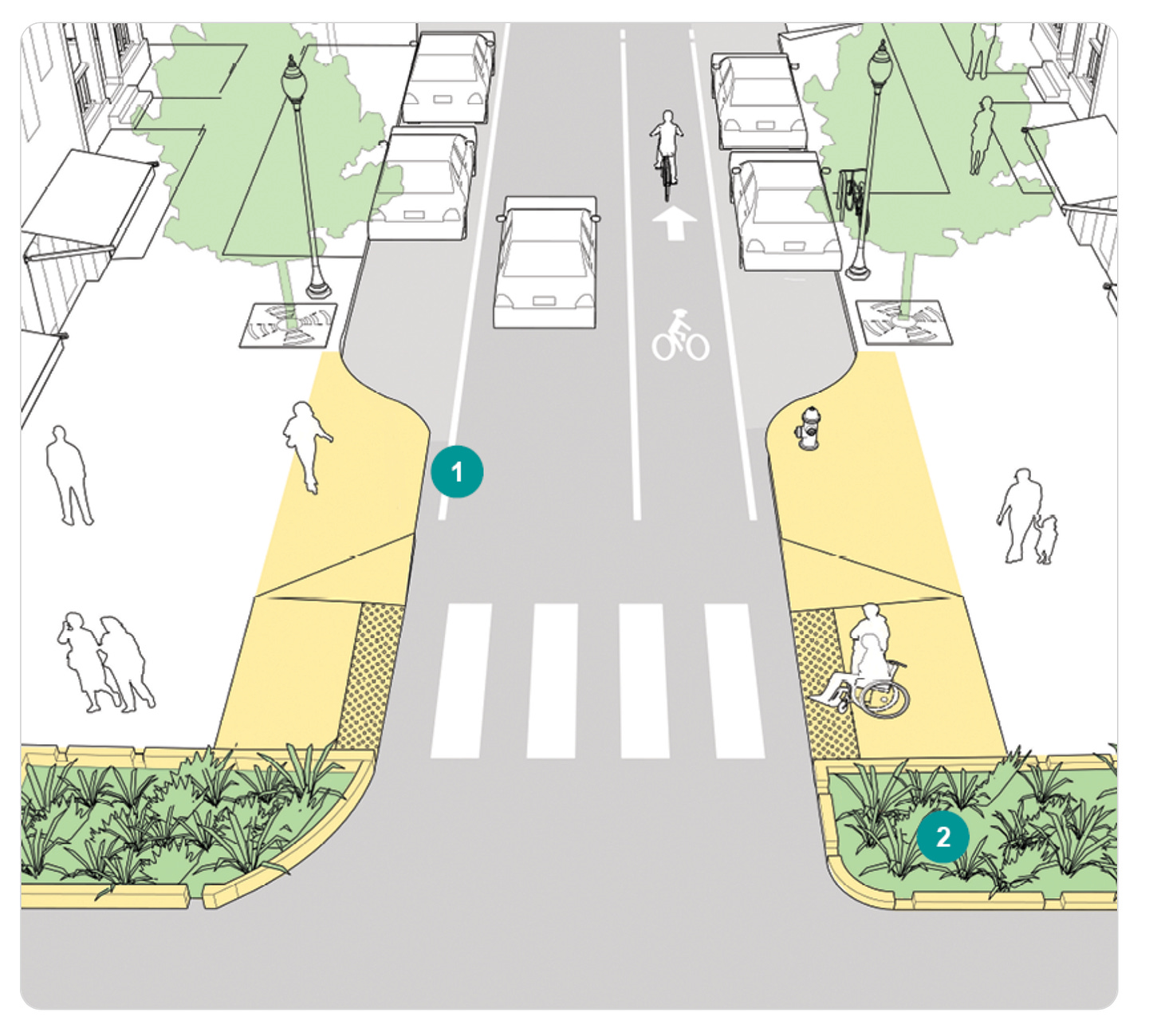

Short, safe crossings

Great streets put a special emphasis on pedestrian crossings. Intersections should be compact, so that crossings are short. Ideally crossings should also be level, meaning cars have to actually drive up onto the intersection like a giant speed bump. That signals to everyone that pedestrians have priority.

Shared streets

In cases where there’s low need for car access, either because it’s a quiet residential setting, or a moderate to high density mixed-use setting where most people can walk to their destination, we could reach for the gold standard of street design: a shared street.

These are rare in North America, but I hope we’ll see more of them in the future.

The City’s Role

Everything in this section is the City Government’s job. It needs to plan the network of roads and transit such that streets are not over-burdened with traffic. And it needs to design the streets to ensure safe speeds, safe intersections, and protection from traffic. There’s an extensive body of research on how to do this. For a deeper dive, I recommend the NACTO Urban Street Design Guide.

The public interface

Given we have safely handled the cars (or have limited/no car access), the next element we need to get right is the public interface, i.e. the sidewalk and all the space between the curb and the edge of the public right of way. It’s not hard to get the walkway right, but a few critical functional requirements must be met.

Continuous paths (clear of utilities)

This is the most obvious requirement, and yet one that is violated surprisingly often: Sidewalks should be continuous. They shouldn’t be interrupted by utility poles or other fixed objects.5

Examples of failure:

Where they exist, or can be built, alleys are a great solution for power and telecom lines, as well as parking and trash pick up. Having the utility space in the back takes this burden off the street and makes it nicer overall.

Sufficient walking space

A walking path should be at least wide enough for two people to pass.

Five feet is usually enough for two adults, but more is much nicer. At ten feet there’s enough space for small groups to pass each other without much contortion. Strolling is much more pleasant when you can hold hands with your partner, your kids, versus having to line up single file to pass other people.

Let’s talk about planter strips. I think planter strips are overrated, and in most cases it would be better if there was a wider sidewalk instead. You can see in these two examples, this five-foot sidewalk isn’t wide enough for the volume and the planter strip is pretty sad.

Meanwhile, you can still have tree wells in wider sidewalks, and the result is a much more practical walking surface.

I think some people feel like a 10 feet or wider concrete sidewalk feels too barren, but you can make this much nicer with mixed materials.

If budget allows you can also incorporate planters and other decoration into the walkway to create a greener space while still maintaining more than a 5-foot walking space.

There’s one tradeoff here: you don’t need a massive sidewalk when a place is low density. If it grows, you want to be able to expand, but you don’t want to kill the trees or mess up the direct access. So one approach is to make the sidewalk further away from the curb and leave generous tree planting spaces a bit further apart but skewed towards the curb. Then, if you needed to later, you could widen your sidewalk into the planter strip without encroaching too much on the trees.

Surface quality

The street and sidewalk surfaces should be well-maintained, such that potholes or other hazards don’t cause people to trip and fall, or have to pay constant attention to the surface to avoid doing so. The walkway should be clear of plants and branches.

Drainage

The walking surface needs to drain properly, especially in places that see heavy rain. In winter, where relevant, the surface needs to be kept clear of snow and ice.

Lighting

At night, the street needs to be well-lit. Creative and artistic lighting is also a chance to make a street far more beautiful. There’s enough here for an entirely different article, so I’ll suggest this one as a good read.

Sun and Shade

A great street should have shade so that people don’t overheat in the summer. In the winter, there should be sunshine so it doesn’t feel as cold.

As it happens, we have this marvelous technology called deciduous trees that create shade in the summer but drop their leaves and allow sunlight in the winter. Street trees are a great idea, and should be planted widely.

Seating

Having space to stop and sit for a while makes the street a nicer, more sociable, and more inclusive street.

In his classic work, “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces,” William Whyte sung the praises of the moveable chair:

Now, a wonderful invention--the moveable chair. Having a back, it is comfortable; more so, if it has an armrest as well. But the big asset is movability. Chairs enlarge choice: to move into the sun, out of it, to make rooms for groups, move away from them. The possibility of choice is as important as the exercise of it. If you know you can move if you want to, you feel more comfortable staying put. This is why, perhaps, people so often move a chair a few inches this way and that before sitting in it, with the chair ending up about where it was in the first place. The moves are functional, however. They are a declaration of autonomy, to oneself, and rather satisfying.

Cities should allow businesses to put out moveable chairs and tables, so long as they’re not blocking the middle of the walkway.

The City’s Role

As in the previous section, designing and maintaining the public interface is primarily the city’s job. At minimum the city needs to maintain a clear, continuous walkway that’s wide enough, drains properly, and is lit at night. Above that, providing creative lighting and street trees will enhance the utility and beauty of the street.

Note that while I’ve split the design of the travel lanes and utilities from the public interface, most cities are going to have a public works department that treats all of this as a single exercise: they’ll design and build travel lanes for cars as their main concern, and may also install sidewalks as an afterthought. Pragmatically, it makes sense to have a single department that designs and constructs the public right of way, but public interface design should be given much more weight than is typical today.

The private interface

Given we’ve adequately handled the public right of way, with safe conduits and a good walkway, we can turn our attention to the other half of the interface: the private properties that attach to the street.

Streets are practical public spaces. For a street to be great it first needs to be useful, or people won’t go there. Once a street is useful, the goal should be to make it interesting.

Active Use

The ground floor of properties facing the street should be actively used — meaning it should not be used just for utilities or parking. The ground floor is sufficient, but the first two floors is better. Higher than that is not very perceptible.

Having a wide variety of uses in close proximity (aka “multi-use” or “mixed-use”) is also a good idea, as it makes the street more useful and potentially more interesting.

Pedestrian Access

Streets should have direct pedestrian access from the public interface to the private property. In other words, the property should have a front door, and that front door should be directly connected to the street. In some cases this could be a shopfront that opens onto the street, or it could be set back and connected via a walkway.

Car access is also important — specifically, it’s important that car access not excessively interrupt the pedestrian space. Too many driveways ruin the walkway and the walking experience. While on-street parking is fine, driveways should be minimized, and pedestrians should never have to cross a parking lot to enter a building. Where parking lots are required, they should be behind or beside a building, not in front (Alleys make this much easier).

Access Point Spacing

The next step up from direct access is to have more frequent access points. Because walking isn’t very fast, a street is more useful when it connects more destinations in the same amount of linear space. That means it’s more interesting to walk through a place with lots that are narrow and deep vs. wide and shallow. This is true for both residential and commercial uses.

Access points further apart are okay when necessary, but the farther apart the access points are the more sterile the environment will feel. As access points get more than 100 feet apart people will increasingly feel that they aren’t meant to walk there, so they won’t.

One access point every 50 feet is enough to be interesting, but closer together is even better. In a commercial or mixed-use context, the most vibrant commercial streets tend to have almost continuous access.

Orientation

Logically extending the idea of more frequent access points, spaces should be oriented with the narrow side to the street when possible.

Both homes and businesses naturally have spaces that are more public and more private, you want to give plenty of room for privacy in the back, don’t make people stick the private space along the street frontage. This is a common problem with retail space that lines parking garages — it ends up having lots of “back of house” stuff in the front, either screened off or open to the world to see.

Transparency

Ideally, building frontages should be partially transparent, which is a fancy way of saying they need windows. It’s probably obvious that blank walls are uninviting, but it’s surprisingly common for businesses that have windows to use frosted glass or keep curtains drawn, etc. There’s a tradeoff between the inviting openness of a shopfront or a lobby, versus the need for private space. This is one reason to prefer lots (and buildings) oriented with the narrow side to the street — the interior is inherently private.

For houses and townhomes, front porches and stoops create a welcoming semi-public interface, while the ground floor being slightly elevated improves the privacy inside the home.

Conversely, for commercial space, it’s far better to have at-grade access. Elevated commercial spaces are less accessible and will require ramps to meet ADA requirements, creating friction between the public space and the business.

The City’s role

To create great streets, the city should regulate the private interface. I hope these examples have given you an idea of what that might look like.

At minimum cities should set standards for active use on the ground floor and direct access from the street. Beyond that, I would recommend cities create guidelines and incentives for orientation, maximum access point spacing, and transparency.

Note that these kinds of requirements are generally found in form-based codes, but you may notice that in all this discussion I didn’t have anything to say about the architecture of the buildings themselves.

I would not generally recommend requiring particular architecture styles, details, or signage. These put a high burden of review and add a lot of subjectivity to the approval process. In practice, trying to “require beauty” becomes the same thing as “requiring luxury,” which is inherently exclusionary.

Instead, I would encourage cities to do things like publish pattern books and pre-approved plans, and find ways to incentivize the kind of architecture they want to see. But buildings come and go; if a place is highly functional then mediocre buildings won’t kill it.

Lastly, I think cities should favor public interface requirements over strict single-use zoning. Making the buildings fit together nicely does a better job achieving “compatibility” with “neighborhood character” than micromanaging land use.

Recap / Checklist

To create the conditions for a great street, we don’t necessarily have to accomplish everything on this list. Most great streets of the world still have some “warts” in places — a building that’s too wide, an empty storefront, a section of blank wall, or sidewalks that are too narrow at points. That’s okay. The goal should be to check as many of these boxes as we can. The more of these guidelines a street meets, the more likely a great street will emerge.

And so you don’t have to scroll back through all of that to remember, here’s the checklist:

For the Conduit:

Narrow Lanes

Short, safe crossings

Shared streets (where feasible)

For the Public Interface:

Continuous paths (clear of utilities)

Sufficient walking space

Surface quality

Drainage

Lighting

Sun and Shade

Seating

For the Private Interface:

Active Use

Pedestrian Access

Access Point Spacing

Orientation

Transparency

These fifteen ingredients are all it takes to make magic.

When it all comes together

The space/time paradox of cities is that people trade space for serendipity.

Great streets are places for people to come together, to bump into each other and have an unexpected conversation.

Try to walk past an ice cream shop without smiling at least a little bit.

Or this cat cafe — even as someone highly allergic, it makes me happy that this exists.

These are the simple joys of neighborhood life, the beauty of the world we make together.

The city can’t do this alone, nor can any individual resident or entrepreneur. Serendipity is a wildflower that blooms where the conditions are right. But the conditions are not mysterious or difficult to create. Human societies did this instinctively for millennia before we decided to do things differently.

We could make different choices, and make great streets our default again. Let’s do that.

Thanks to Mike Riggs, Hiya Jain, and Abby ShalekBriski for feedback on drafts of this essay.

Jane Jacob’s masterpiece, The Death and Life of Great American Cities can be read both as a rallying cry against contemporary car-centric redevelopment in cities, and a sort of eulogy for the way city streets historically worked. Her work inspired much of the early resistance to freeways and urban renewal, and influenced Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, which further moved the public mood against redevelopment.

Note that even though this space is owned by the city, cities often expect the adjacent property owner manage it (ie they expect you to mow that planter strip in front of your house). But, in busier urban areas the city may play a more active role.

We’re used to it, but when you stop and think for a moment it’s obvious that the most dangerous thing we interact with on a daily basis are the at-grade conduits where multi-ton metal boxes operated by tired and distracted people whizz past unarmored pedestrians. Try going for a walk with a toddler and feel your adrenaline level rise!

Things got this way because mid-century engineers took the principles of highway design and tried to apply them universally. This promoted high speed traffic in neighborhoods and commercial corridors, where local access is the primary need, and high speeds are inherently unsafe.

Thankfully, in the past 25 years we’ve made tremendous progress in developing safer design patterns for streets and propagating that knowledge. We have a long way to go in terms of implementation, but better practices are becoming the norm.

This is why we need both streets AND roads, obviously you can’t get from A to B very well if every path was limited to 20mph.

Overhead power and telecommunication lines can be unsightly, but burying them is expensive and makes them harder to maintain. In my experience, as long as the poles don’t block the sidewalk, overhead lines don’t matter a whole lot. They’re really only a problem for cameras — our eyes see right through them! Newer phones come with “AI erasers” that work pretty well, I wouldn’t be surprised if “remove power lines” became a built-in function in the near future as well.

Really fun post Andrew. The one part I’m nervous about: Cities setting standards for active use and direct access. Why not do incentives for everything rather than mandates?

My skepticism comes from how I’ve seen cities try to regulate ground floor uses. Forced commercial requirements that become vacant dead space; arbitrary design requirements intended to “activate” ground floors but end up creating more dead space

If cities invest in attractive public spaces, I suspect private developers will have a much stronger incentive to build engaging ground floors. (And cities can also offer money for use of preapproved designs or other subsidy, whatever they like.) If cities try to regulate their way into attractive ground floors, I worry we’ll end up in a place not so different from the one today, a place where overzealous planners and council members use bizarre, inflexible standards that make an inflexible environment

Maybe I’m just a fundamentalist, but my sense is that the old main streets didn’t arise because planners regulated interfaces, they arose because building them that way made obvious economic sense. Sure, cars + auto-oriented city planning transformed the economics, but cities can potentially still revive the old economic logic by providing the foundation you lay out in the rest of the piece

all good points and I get them all, but we must talk about the economic aspect:

https://exploringhumans.substack.com/p/do-you-hear-the-scream