The long history of shaping our cities

If cities are emergent, how do we influence them?

In the last post we concluded with the idea that cities are complex adaptive systems that emerge at convergence points in the four environments. Therefore, cities are not like individual buildings we design then construct. Rather, cities are natural ecosystems that have an inherent, organic pattern of growth and life.

So we know that cities aren't designed, but of course, modern cities aren't wild ecosystems either. To complete the mental model, it's best to think of cities as gardens; we don't have direct control, but we can shape them depending on the level and kind of effort we're willing to make.

We have a long history of shaping our cities, but the tools we use have changed dramatically in the last hundred years, resulting in profound divergence from the historically normal pattern. Understanding this history is extremely helpful for imagining what new paths we might take in the future.

We can divide this history into three major stages of development.

The Landmark Stage

The landmark stage is defined by low state capacity. With limited state capacity, the government does not (cannot) micro-manage development. Streets and spread organically as the city grows, land use is finely mixed, buildings come in all shapes and sizes, but mostly simple and mostly larger toward the center.

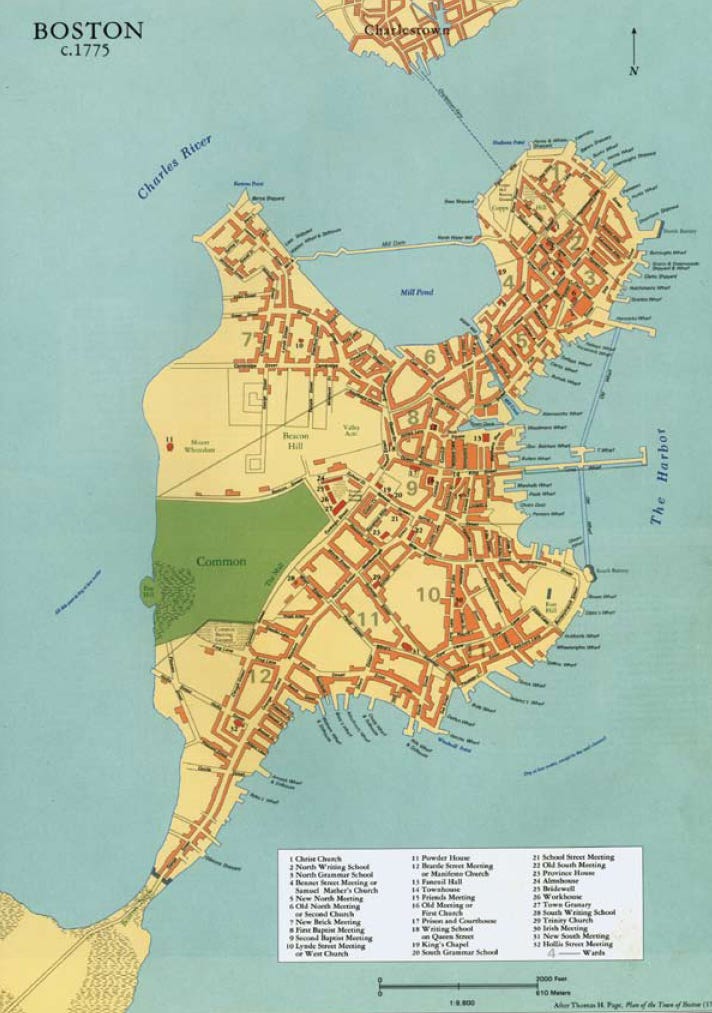

Most cities for most of human history have operated in this mode, and the cities forms that emerge have been remarkably consistent for thousands of years. Notice how similar the forms of Colonial Boston and Medieval Venice are:

In the Landmark stage, the shape of the city is largely organic, but steering does happen via landmark development. The public resources are pooled to create a temple or town hall at the center, or to build the city wall. In the larger cities a grand avenue may be cut through the organic city fabric to connect two landmarks. In major capitals there are more landmarks and grander public spaces.

Landmarks create substantial attraction, so more people compete to own the land next to the landmark or the grand avenue. Over time more wealth concentrates along these convergence points in a virtuous cycle.

Cities following this pattern are messy but vibrant. This form is still predominant in the developing world today. The pattern is well-evolved to effectively serve these human needs, and should arguably be considered the natural form of human settlements.

The Landmark stage city centers that have survived to the present in wealthy countries have such attractive power that they're considered tourist attractions.

The Planning Stage

With rising state capacity, cities can do more than just build landmarks, they can organize development in ways that deviate from the pure organic pattern, or are super-imposed on the organic pattern.

We see early examples from the ancient Greeks and Romans, organizing new cities with orderly street grids. The Romans in particular developed a formal approach to organizing cities, when they conquered a city they often reorganized its public realm. For example, in Florence they built a central public gathering space (forum) and extended a north/south (cardo) and east/west (decumanus) road through the city.

The most famous example of planning-stage superimposition are Haussmann’s Parisian boulevards, imposed over the organic city by the military might of Napoleon III.

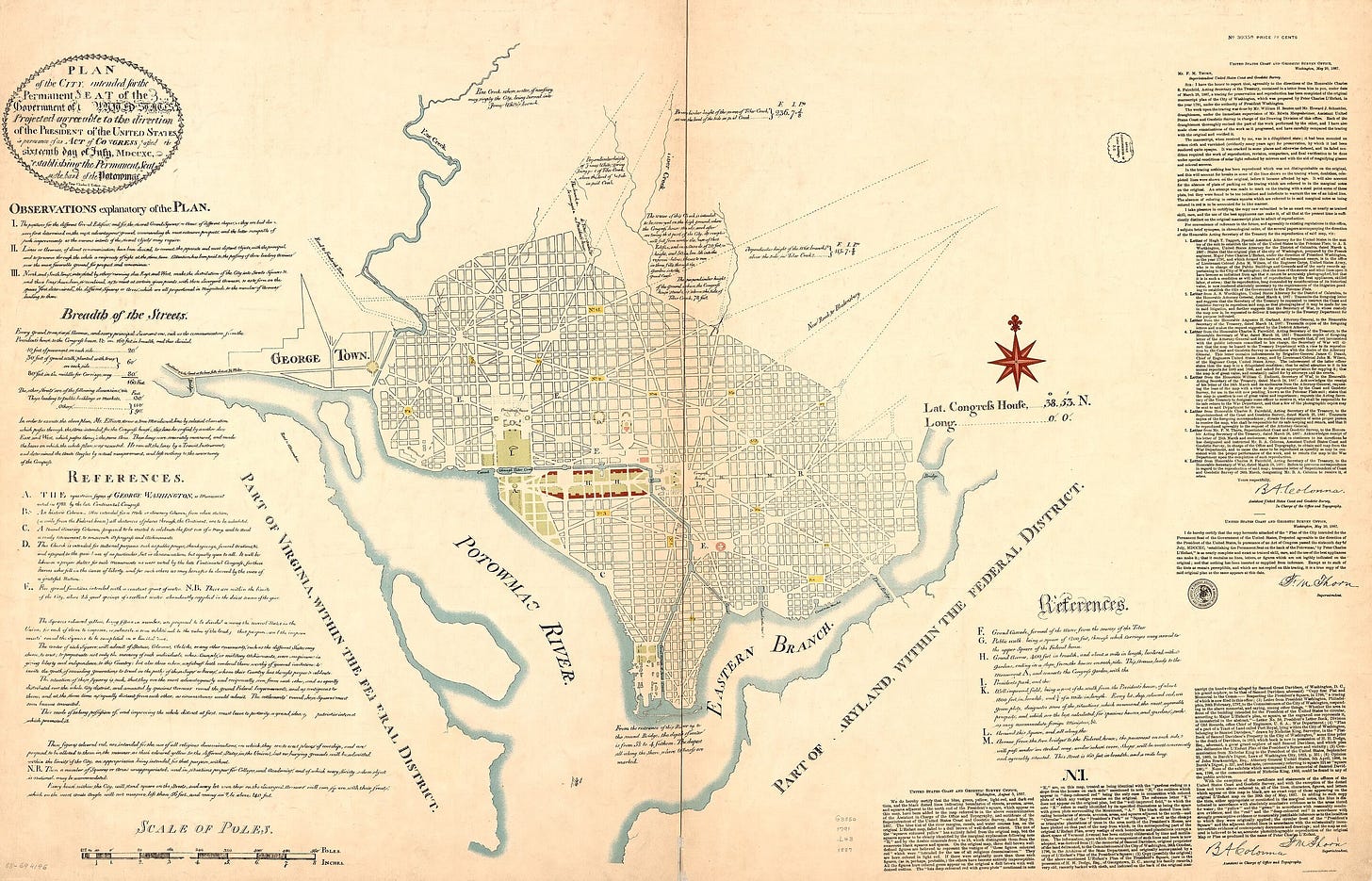

It's historically less common for cities to be created on purpose, but the colonial and industrial period is an exception. Most of the colonial and industrial age settlements in the Americas started with a central green or square and a main street embedded in a simple grid. In a few cases the plans were more ambitious, the peak example being L'Enfant's plan for Washington DC.

These efforts are all examples of Physical Planning, where portions of the public space were intentionally designed. The private space (most of the city: the people, the buildings, the businesses) still emerged organically over time, but the resulting city is more coordinated and orderly as it orients around the public space. During the 1800s this gridded central city pattern had become so prevelent in North America that it became a cultural norm.

By the 1800s private capacity had increased singificantly, and development patterns began to change. While organic lot by lot, building by building development still happened, new land development businesses emerged. These early land developers did largely the same thing they do today: take undeveloped land (typically farms), subdivide it into hundreds of lots all at once, build streets, and sell the lots.

Because the grid pattern is useful and easy to extend, and because it had become a cultural norm, the larger scale development emerging outward from planned city centers tended to follow and (imperfectly) extend the grid. Thus, across North America we see many cities with grids extending for many miles beyond the original plat.

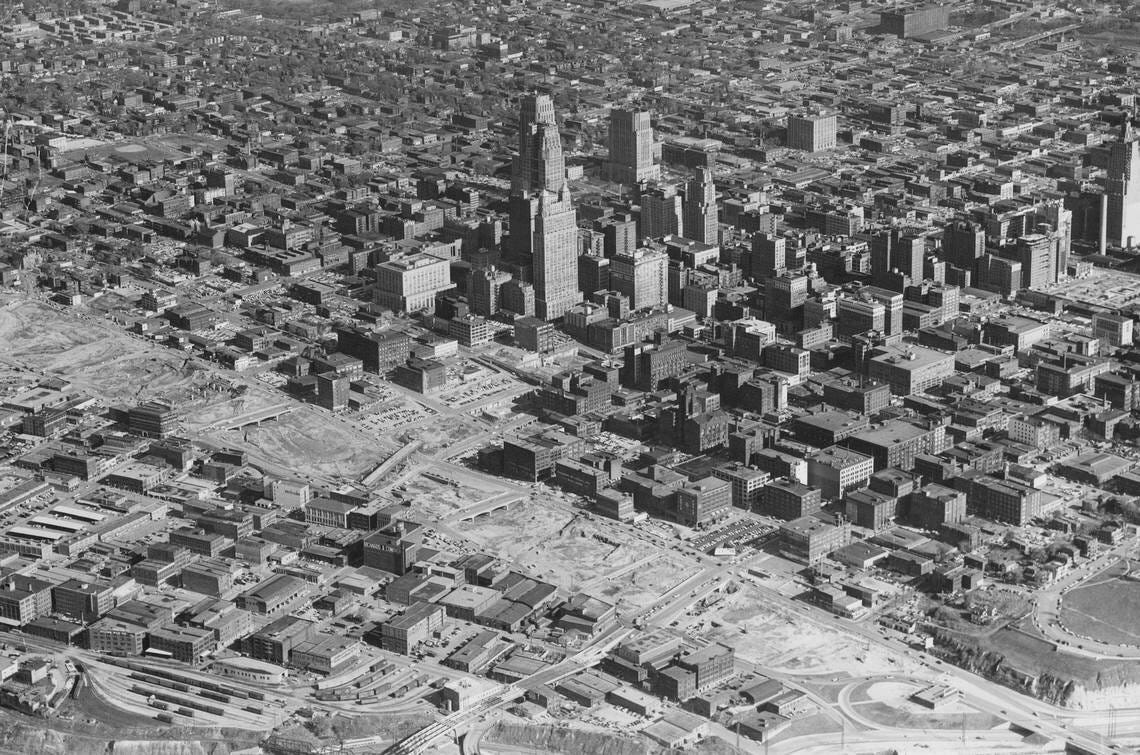

The Planning stage has produced many of our most beautiful and functional urban environments, but unfortunately in the post-war era we took this approach too far. The last large-scale example of physical planning was the demolition of huge sections of American cities to install the Interstate Highway System.

While freeways tremendously improved transportation across the country and powered a generation of economic growth, the scars they left on our cities led to widespread backlash that significantly contributed to cities abandoning physical planning as an approach -- a topic we may explore in more detail another time.

The Regulatory Stage

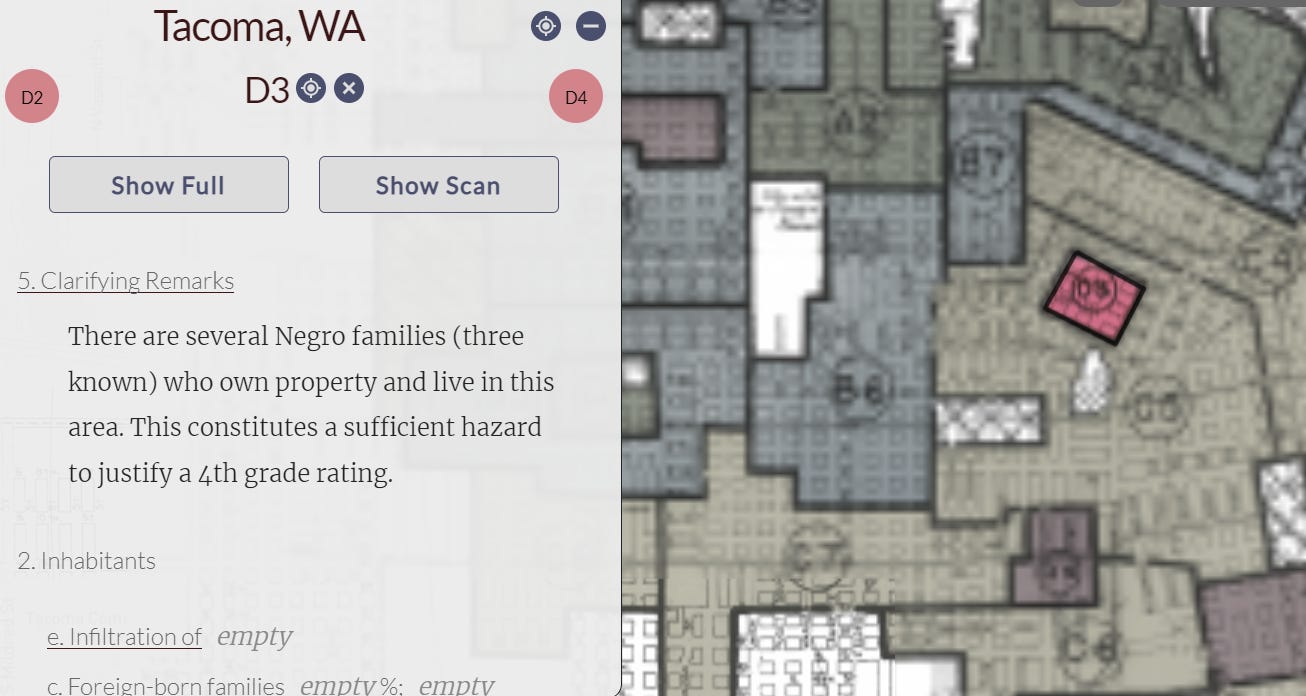

With high levels of state capacity, micro-management of private activity became possible. From 1900 to 1950 cities in North America spent less energy designing the public realm and more energy writing regulations limiting what individuals could do with their property. State and federal governments programs magnified this shift via federally-subsidized mortgages and the ruinous practice of redlining that came with it.

These regulatory and financial systems impose new constraints and incentives on everyone living in a city. Taken together, our municipal and state rules create something like a Suburban Operating System, which defines what is possible (and practical) in our cities.

Significant private capacity is required to raise the capital and spend the substantial time required to comply with these regulations and get anything new built. We’ve adapted to these limitations by first by delegating almost all development to specialized companies, and later by financializing real estate. As a result our cities have morphed into their current suburban form.

A better balance

Today’s steering apparatus is a complex legal and financial system that constrains what individuals can do. It's hard to fix local problems within this system. How do you use regulation and finance to clean up a sidewalk? Cities try, but this isn’t easy.

Pressure to reform the system is building, and significant changes are happening. There's a role for landmark development, for physical planning, and for regulation, but we need a healthier balance than we have today. In future essays I'll explore what that balance might look like, and how we might get there.