How cities block affordable housing

When land prices are high and incremental development is prohibited, there's no good path to build affordable homes

On his campaign website, Denver Mayor Mike Johnston leads with this call to action on housing affordability:

More than 50% of Denver voters can’t afford to live in Denver today. Families who have been here for generations are being pushed out, as well as the teachers, nurses, and first responders who serve our city. Over the last decade, the cost of housing has exploded for both renters and buyers: the average cost of a home is nearly a million dollars, and the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment is $2,250. Nearly 50,000 households pay over half their income to rent. We need sweeping, ambitious change to put Denver back on track.

After taking office, Johnston championed a sales tax increase to raise $100M to build affordable housing, saying “If this does not pass, we’re probably looking at 25,000 families being displaced from Denver over the next decade.” But the tax increase didn’t pass.

“The voters said we don’t want to invest more,” Johnston reflected this summer. “We said, we’ve got to find more ways to do it without that investment.” The Mayor is now promoting for a tax rebate for developers who build lower priced units.

But what if I told you the city could unlock thousands of units of affordable housing, for free, by changing a few words on paper?

In the last post I modeled development on a real site in Denver, and asked what it would take to build an affordable house. The modeled showed why it’s challenging, but also that we could do it — except that Denver’s land use regulations don’t allow it.

Today I’ll walk through those regulatory barriers in more detail:

First I’ll take the model from the last post and show two different design options for how it could be built

Then I’ll walk through the major regulatory barriers that stands in the way, and show how they prohibit the design of the project.

This is a real world example in Denver, which means I’m looking specifically at Denver’s zoning code. But Denver employs most of the common regulatory barriers to affordable housing, so the takeaways from Denver generalize broadly.

An affordable design

First, a quick recap of the development model:

To be affordable for a person earning Denver’s median income, a newly built home must sell for $400k or less.

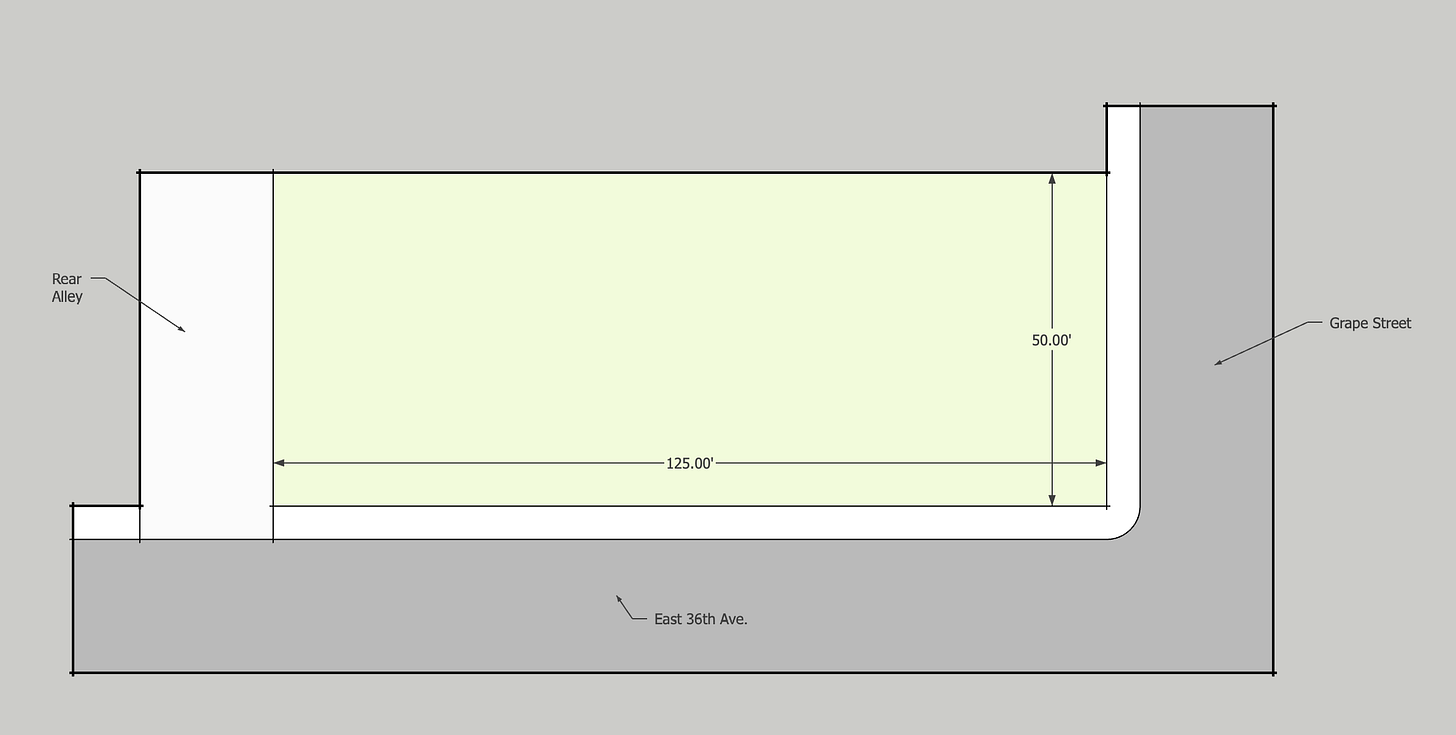

We’re modeling a specific, typical lot in Denver: 3601 Grape St.

Given the high land price in Denver, and the high cost of new construction, the model shows that the best way to achieve our target price is to build four 800 sqft, two bedroom units on the lot.

Throughout this post I’ll continue to refer back to this model — so if you want to see where all the numbers come from you might want to read that post first.

To come up with a design we start with the lot we have to work with:

The lot is on the corner of 36th and Grape Street. This is a very common lot type in Denver. As it’s currently oriented toward Grape Street (on the right), we would say the lot is 50’ wide and 125’ deep, with an alley in the back. But, as a corner lot, we could also think of it as 125’ wide and 50’ deep, with an alley on the side.

Setting the development rules aside and focusing on affordability, I think there are two obvious options to fit four homes on the lot.1

Program 1 — Rental four-plex

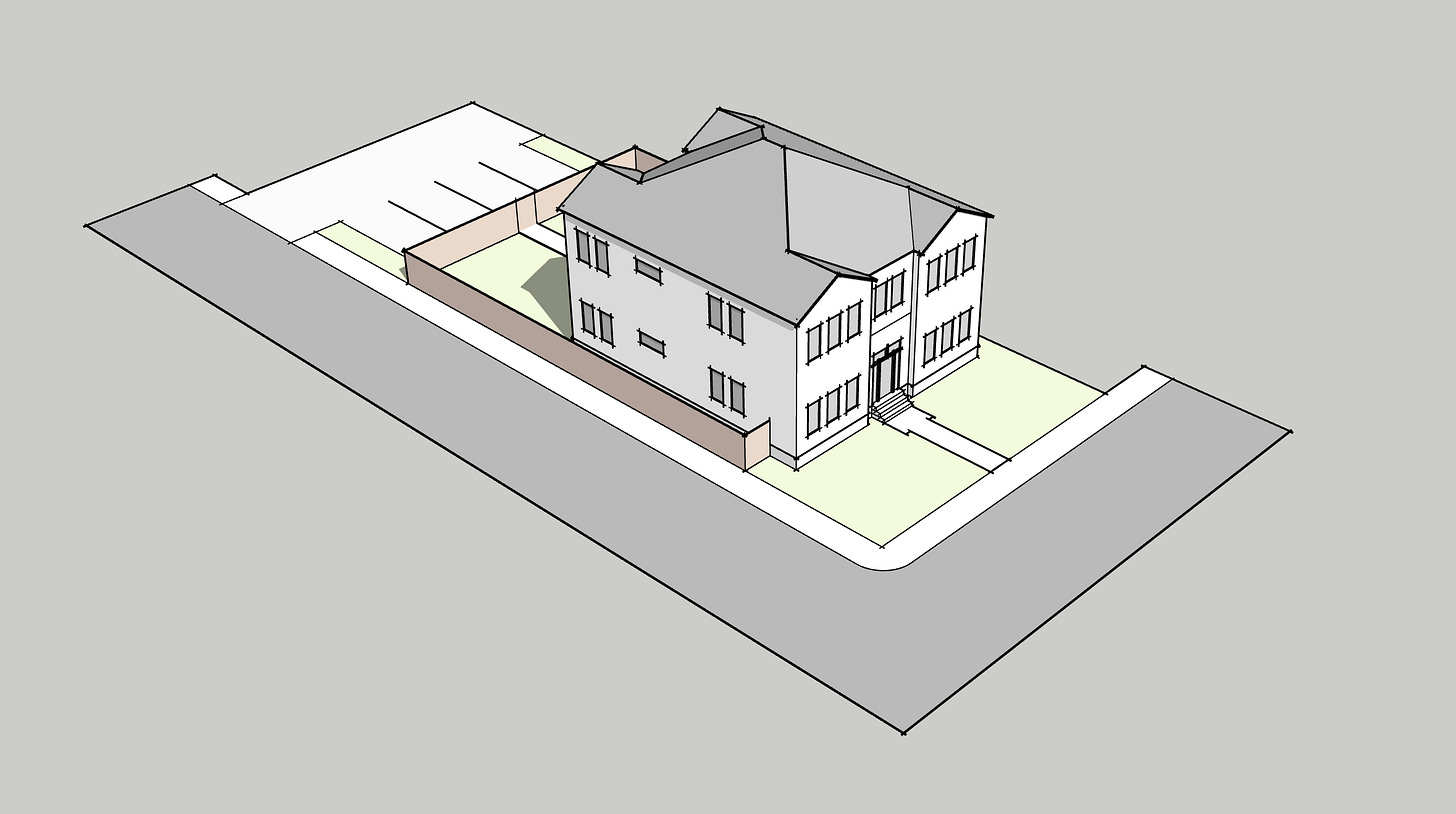

The first program is to build a four-plex, made to look like a large house facing Grape Street, with the interior divided into four apartments. Each apartment would be an 800 sqft, 2 bedroom unit.

We could sell these as condos, but it’s more complicated and less popular with buyers, so this design would probably work better as a rental property. But given the cost of the project, the rent should still come out below our target of $2453/mo.

Program 2 — For-sale starter homes

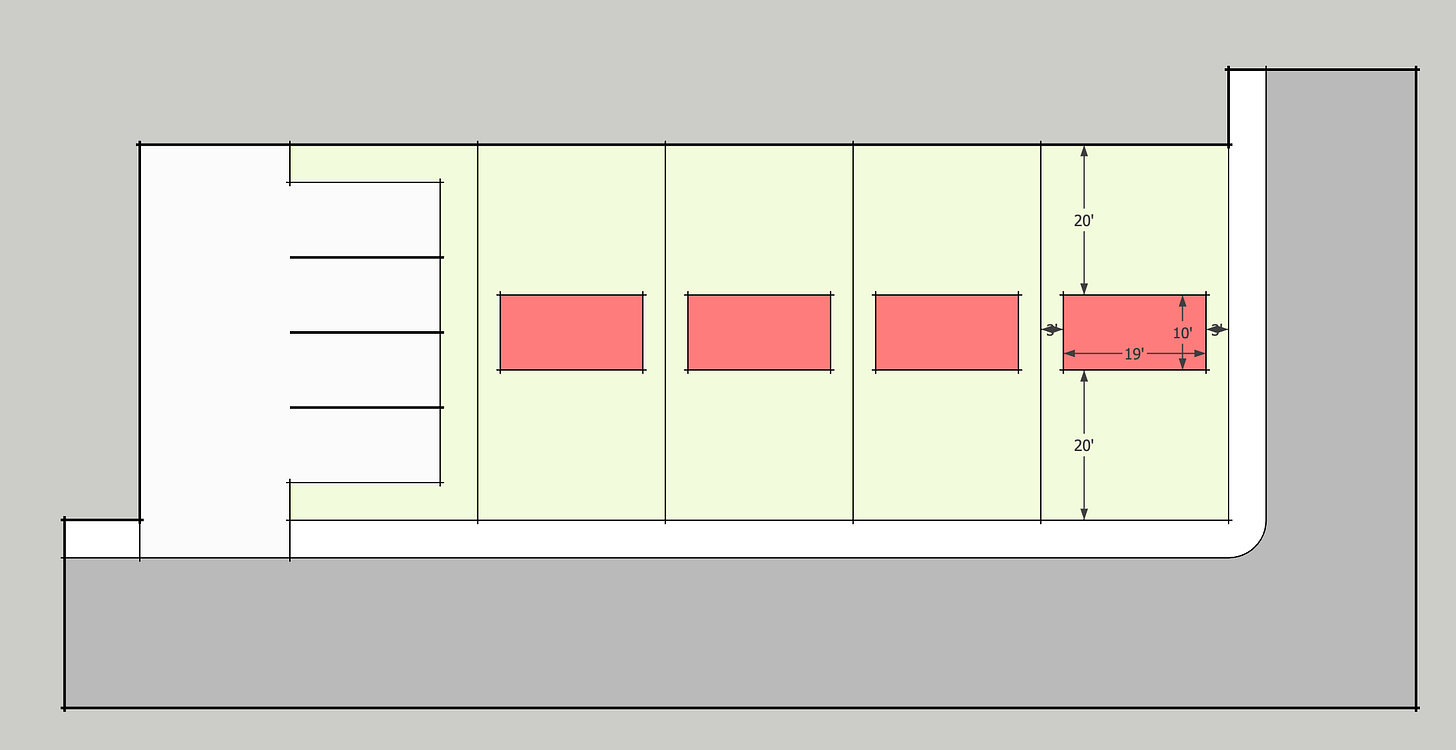

The second program would be to sell four small starter homes. We can take advantage of the fact the lot is on a corner and build 800 sqft cottages facing East 36th Avenue. To make this work, each cottage would get a 25’ x 50’ lot, and we’d have a shared 25’ x 50’ parking area next to the alley.

Denver has thousands of small historic homes on narrow lots like this, so these would be in-character for the city. One difference, the historic homes are usually on lots that are 100-125’ deep, giving a back yard behind the house. Given today’s high land prices, we can’t offer a big back yard within our budget, so these homes would instead have space for a small garden.

Regulatory barriers

I previewed in the last post that Denver’s code won’t allow us to build either of the programs we’re interested in. To understand that, let’s walk through the five most common regulatory barriers one by one and see how they affect our building plan.

The Grape Street lot is zoned E-TU-B, which in Denver’s system means residential use, allowing up to two units, with a minimum lot size of 4,500 sqft. Denver has an additional wrinkle that many of the requirements also vary depending on the building type. Rather than go into this in great detail, I’ll use the rules for the “Duplex” building type as the closest match to the designs we’re interested in.2

Working through the zoning code, we’ll see that Denver has all but one of the most common barriers that prevent more affordable housing from being built.

(1) Unit Count

The first and most straightforward barrier is the unit count restriction. Unit count limitations explicitly cap the number of dwelling units allowed on a property regardless of lot size or building size, often restricting properties to single-family homes or duplexes, specifically to prevent the construction of multi-family housing.

Our starter homes concept features one unit per lot, so it doesn’t run into this barrier, but the lot is limited to “two unit” housing, so our four-plex program is ruled out.

Perhaps we could split the lot in half and try for two duplexes?

(2) Minimum Lot Size

The next problem we run into is that the minimum lot size in this district is 4,500 sqft. We have 6,250 sqft, which isn’t enough to split in half. This requirement rules out both programs.

But suppose Denver lowered the minimum lot size to 3,000 sqft? That would still rule out the starter homes, but it would let us split the lot in half and build two duplexes. If Denver was more ambitious, it could lower the minimum lot size the 1,250 sqft, which would allow the starter home program.

As it is, the rules have already eliminated both of our design concepts. But what if we waived the unit count and lot size requirements, what barriers would we hit next?

(3) Minimum Lot Width

While 15’-25’ wide lots are very common in historic neighborhoods, many cities today require a minimum of 50’ width. Denver requires lots to be a minimum of 35’ wide in this zone. This wouldn’t interfere with the Four-Plex design, but it would rule out the 25’ wide lots we’d need for the Starter Homes.

Well, what if we got rid of the minimum lot width as well?

(4) Setbacks and Maximum Lot Coverage

Most zoning codes require “setback” distances: space that buildings must be kept back from the front, sides, and rear of the lot, as well as lot coverage maximums.

On the Grape St. lot the front and rear setbacks are 20’.3 The side setbacks and lot coverage requirements are based on the lot width: the Starter Homes would require a 3’ side setback and a maximum lot coverage of 60%, the Four-Plex would require a 5’ side setback and allow a maximum lot coverage of 45%.

For the starter homes, after taking out the 20’ front setback, a 3’ side setback, a 20’ setback, we’d have a buildable area of 19’x10’, too small to be useful.

But even if there were no setback requirements, our design specifies an 800 sqft house on a 1250 sqft lot — that’s 64% coverage. We’d have to shrink the houses to 750 sqft to comply with the 60% lot coverage requirement, or redesign them as two-story homes with smaller footprints.

The Four-Plex design fits within the 20’ front and rear setbacks and the 5’ side setbacks and covers 1,850 sqft, or 29.5% of the 6,250 sqft lot.

(5) Parking

Since we’ve just illustrated all the ways Denver’s rules are blocking more affordable housing, it’s worth highlighting one common barrier Denver recently removed: the city dropped its parking mandates this summer.4

Many cities require two spaces per home, which would mean 8 spaces for these designs. That requirement would rule out the Starter Home concept, and would make the Four Plex very difficult.5 Removing parking mandates was an important step for Denver to improve the viability of housing on smaller lots.

Cities get what they require

Walking through this example becomes a little bit absurd because we considered the various regulatory requirements one by one, when in reality they’re part of a bundle designed to go together and reinforce each other.

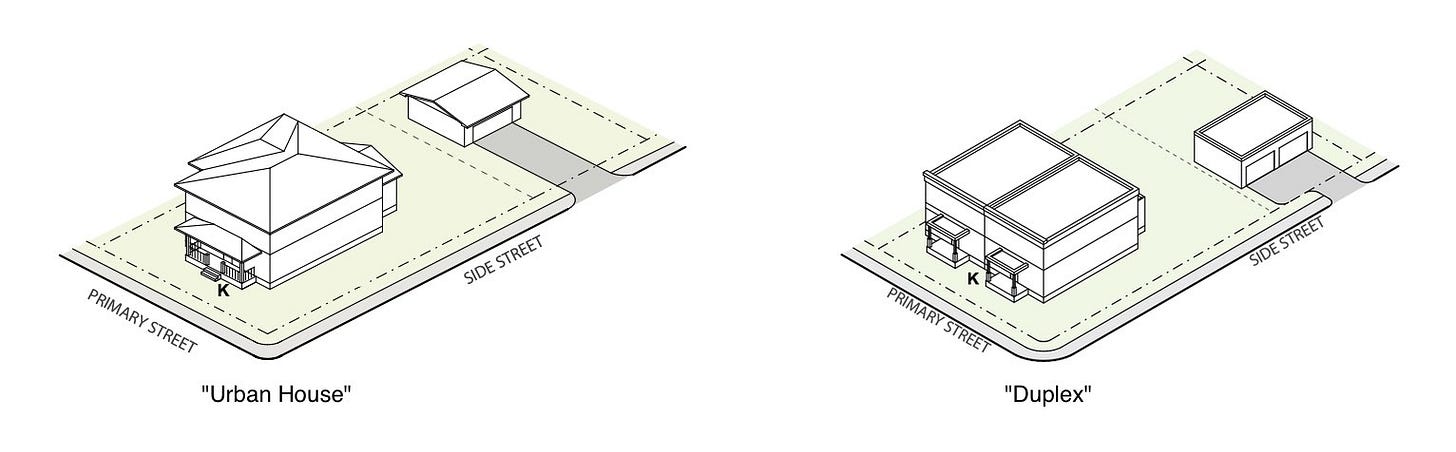

At 3601 Grape Street, the city has mandated a specific outcome: the lot is not meant to be split in half, it’s meant to contain either a single house or a duplex. That building is meant to have an ample front and back yard, and a moderate side yard, so that it “looks like” a conventional house. The city kindly provides illustrations of what they’d like to see:

And you may think, “wait a minute, that actually seems like it would be pretty nice, why don’t we just build that?” You can see why people might like a code that requires this. But remember the model from the last post? We’re trying to hit a sale price of $400k and this lot costs $350k. The zoning code requires a large amount of land per home, and there’s just no way to make an affordable house if you start with requiring lots of expensive land — even if the house itself is was tiny.

When land is expensive, the easiest lever for affordability is to fit more homes on the same amount of land. By preventing that, or requiring an onerous and uncertain rezoning process to do it, cities effectively require higher cost housing.

And our elected officials know this! I opened with a quote from Mayor Johnston’s campaign site. Here’s another quote from further down the page:

To meaningfully achieve housing abundance in Denver, we must add density in select areas of the city, which is prohibited in many areas by our zoning code. As Mayor, I will explore sensible changes to zoning to help increase density in neighborhoods where it makes sense.

We know it works. The research shows that increases in density—even small ones—lead to lower rental costs.

In Denver, and in any city with high land prices, there are two straightforward solutions:

The simplest change is to keep the building form requirements, but remove the unit count restrictions. If what neighbors care about is the aesthetics of a neighborhood made of big houses with yards, the Four-Plex blends right in. Denver has manyexamples of historic multi-unit buildings that just look like big houses, sprinkled throughout the majority of established neighborhoods.

The next step would be to reduce minimum lot sizes, and revise the lot width, lot coverage, and setback rules to match. Houston famously “does not have zoning,” but it does have all the development regulations we talked about today. When Houston reduced its minimum lot sizes from 5,000 to 1,400 square feet, it led to the development of more than 34,000 new homes, mostly on formerly underutilized commercial and industrial land. More cities should follow Houston’s lead.

The challenge of course, is in the subtext of Mayor Johnston’s campaign message. That we must add density in “select areas, where it makes sense.” But that isn’t a viable approach.

No neighborhood should experience radical change, but no neighborhood can be exempt from change. It is not healthy for neighborhoods to radically transform, uprooting people and distorting established price relationships. It is equally unhealthy for neighborhoods to be locked in amber, artificially stagnating despite market demands or the needs of people within the community.

We can’t solve our housing problems within a paradigm of stasis. Cities need to allow the next increment by right, everywhere, to unlock healthy growth and achieve broadly affordable housing.

Thank you to Sam Enright and Étienne Fortier-Dubois for their feedback on drafts!

These aren’t the only two options, but they’re sufficient to illustrate the model and the barriers it faces

Denver’s zoning is very complex! It has 145 distinct zones (if I counted correctly), divided between six different “neighborhood contexts” and a number of special districts. It’s a unique code with some interesting ideas in it, and is perhaps worth an explainer another day.

If you’d like to see the rules that apply to the Grape St. site for yourself, see Section 4 of the zoning code, and in particular Section 4.3.3.3.D.

Denver has an interesting front setback rule, where the setback is calculated based on the setbacks of the surrounding buildings, rather than being a fixed distance. However in this case the neighboring buildings are vacant lots, so I believe the default setback of 20’ would apply.

For what it’s worth, Denver’s old rules in this district weren’t too bad; just one space per unit. So, in Denver, parking wouldn’t have been the barrier for these design concepts.

Because the lot is only 50’ wide there’s not enough room for an efficient parking configuration. I think you could fit 8 cars if you got clever with a mix of a through lane from the side yard into the alley and a combination of angled and parallel parking — but, I decided not to spend the time drawing that to verify. Years ago, when I worked in urban planning, I had to spend a very large percentage of my time designing parking lots (parking is the binding constraint on many developments, and figuring out a layout that can fit 5-10 more spaces can make or break a project), and I just don’t feel like doing that anymore 🤷♂️.

Great ideas! The setback portion reminds me of something that happened to a friend when she tried to sell her 1906 house here in Portland, OR, last year. She lived in one of the first houses built in the neighborhood. That part of the city was considered rural in 1906. The newer houses were built on top of her existing sewer line. When she wanted to sell last year, the city's rules had changed from when she bought it 25 years earlier. She was forced to move the sewer line.

The setback that is now required for a new sewerline was shorter than the setback of her house to the sidewalk - there was no sidewalk when the house was built, nor the many streets now there, of course. She ended up having to pay a neighbor to put the line through their backyard to get the line onto another street...a street that didn't exist when the house was built.

The whole fiasco ended up costing over $80,000. The price of the house was only $60,000. Once the city designated her sewer line incorrectly placed, she couldn't even rent it. The house, which was there first, was uninhabitable despite the fact that she had lived there raising her son for over 25 years. Absolute madness!

You know. You could even make those 4 cottages 2 stories for probably a nominal increase in price giving a family much more utility on that postage stamp land area..I see you already thought of that shrinking the exterior dimensions to meet land usage constraints. Great article!