A taxonomy of place

Labels for more specific discussions

In the last post I explained why the way “urbanists” use the labels “urban” and “suburban” isn’t actually very descriptive, and suggested we should consider more specific terms. Today I’ll offer an alternative.

In this post I’ll describe three different characteristics of place, each of which plays a critical role in how a place functions. We can think of each characteristic as a scale of sorts, and label the low, medium, and high point. In each case, higher is better. Together, these labels offer a more nuanced taxonomy of place. Among people who have developed a deeper interest in cities and how they work, I hope that these labels could facilitate richer and clearer discussions.

I’ve tried to use terms that are intuitive, and I think these would be easy enough to use in conversations with the broad public, even while I do not expect normal people to learn this taxonomy. After you read I’d love to hear what you think.

Two things to note up front:

This is a taxonomy of developed places, where “developed” means something like, more than 50% of the land is built out, and the population density is greater than 1,000 people per square mile.1

These labels describe places as a whole, meaning neighborhoods, towns, and cities in their general or prevailing condition, not at the level of a single lot or block.

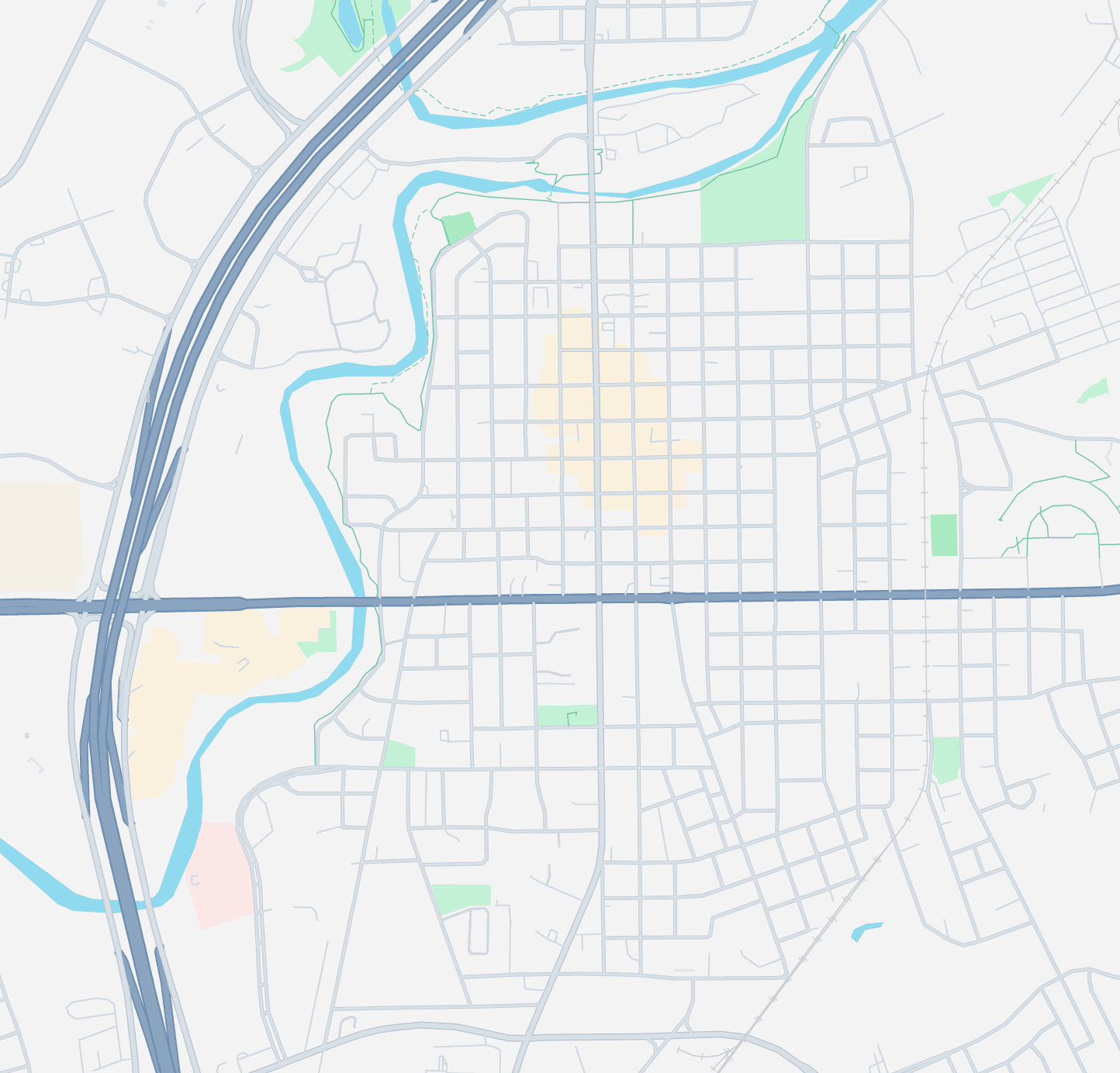

Street Connectivity

The single most important characteristic of a place is its street pattern - not the design (or cross section) but the shape of the network (ie as you see it on a map). What matters is how well-connected the street network is.

We can label three levels of street connectivity:

Disconnected

Typical of suburban areas built after the 1980’s, most development today is intentionally disconnected from the rest of the surrounding area. Subdivisions rely on just one or two connector roads to connect to the outside world, and to the extent the internal streets form a network at all, they’re a fully a closed system. While these developments are not all literally gated, they’re functionally gated. This pattern of development creates long minimum distances between destinations, typically getting to anything outside the development is at least a 5-10 minute drive, if not longer. It also results in traffic congestion on the small number of roads that actually go anywhere, which gets worse and worse with further development.

Sparse

Earlier suburban areas tend to have large blocks and curvilinear streets, but still form a somewhat connected pattern. Walking and biking may be slow if the area is low density, but neighborhood services are often accessible without traversing on arterial roads. Driving is the most practical option, but other modes are still viable. This pattern still tends to concentrate traffic on a small number of major roads, but it handles growth much better than disconnected streets.

Connected

Until the middle of the 20th century, cities tended to be built with well-connected blocks, often in a grid, but also in more organic patterns. Travel between destinations is quick and efficient with relatively direct paths, and with many options to get from A to B, travel is diffused through the network. Every mode of travel is equally viable in a well-connected environment.

Ideally, cities’ street networks would always be well-connected. This pattern is the most flexible and adaptable over time, and offers the most convenience for all modes of travel. We shifted from connected to disconnected street patterns largely because people don’t like excessive high-speed traffic pouring through their neighborhoods, but fortunately we have better solutions to that problem that don’t force every mode to take circuitous routes.

Land use Diversity

The second dimension of place is economic diversity, that is, having a mix of land uses available in close proximity — meaning diversity of the economic activity (residential / commercial / office, etc.) and building type (single family / duplex / apartment, etc.).

We can label three levels of land use diversity:

Single-use

Most greenfield development in the last 50+ years has been single-use, with large residential districts separated from commercial corridors. Not only are vast areas of land restricted to a single use category, most of these residential areas contain only single building type (detached houses) in a narrow band of size and price point.

Multi-use

Multi-use (or horizontal mixed use, if you prefer), is the traditional pattern of cities and towns for most of human history.

This neighborhood in Denver is a good example. In the photo you can see a row of shops with an apartment building directly behind them. The surrounding blocks are predominately lower-density residential, with a mix of detached houses, duplexes, and small apartments. The diversity of land use means many daily activities are sprinkled through the neighborhood, quick and convenient to access.

Mixed-use

At higher levels of development we start to see uses mix in a single lot.

Places should ideally have high land use diversity: Just as monocultures are less productive than diverse ecosystems, human communities are healthier, more prosperous, and more resilient when they contain a diverse mix of land uses. In most neighborhoods and smaller towns, that would mean a “multi-use” mix of housing types with small businesses and neighborhood services sprinkled conveniently throughout. In more developed areas with larger buildings we’d see vertical “mixed-use” as well.

Street Safety

The last dimension of place to consider is street safety: specifically how the design of the street makes it either dangerous or safe for different users. Remember: streets and roads are different, so this question applies to the streets that provide access to and from properties, not highways.

You don’t need any expertise or training to understand street safety, just go for a walk and think about how you feel. Are you worried about getting hit by a car, or tripping and falling, or squeezing past obstacles? Or is the space comfortable and worry-free to inhabit?

We can label three levels of street safety:

Unsafe

Just taking this picture was nerve-wracking. If you can’t tell, that sidewalk is about two feet wide, and the adjacent traffic averages 40-50 mph. Conditions like these are quite common throughout the US.

Safe for Adults

Here we have a fairly standard residential sidewalk, followed by a nice Main Street.

These environments are safe and comfortable for adults. However, as a parent, they’re still stressful with kids, as children aren’t born with a sufficient fear of being run over. Intersections and high speed traffic are the main danger, but the sidewalk itself is safe.

Safe for Kids

In a pedestrian-priority street, kids can safely roam freely. Streets like this are almost non existent in North America, but are becoming more common globally, especially in the Netherlands.

The Dutch call this kind of street a “woonerf,” which means something like “a street for living.” These are increasingly the standard for residential areas in the Netherlands — accessible for cars but designed for very low speeds so that crashes aren’t a concern.

With limited exceptions, our street networks (streets, not roads) should be designed and built with “safe for children” as the goal.

Order of importance

The ideal human habitat is safe, diverse, and well-connected. These aren’t the only dimensions of place that matter, but they’re the pillars of a healthy community. On each dimension, the “middle” label represents a kind of minimum viable place; places that have at least a sparse network, permit land use diversity, and make their streets safe, are well-equipped to adapt to change over time.

None of these characteristics of place are easy to improve, but there’s a clear order of importance:

Street safety is the most straightforward dimension to improve. It takes money and time to rebuild a street into a safer configuration, but cities own their rights of way and have the authority to “just do it” if they want. Tactical urbanism can be a fast, cheap, first step. However it happens, once construction is done, the change is finished.

Land use diversity is more complex. On the one hand, the reason this is rare today is that it’s illegal. City councils have the power to change their laws, and could legalize land use diversity in a single council session at no cost to the public. On the other hand, even if it were legal immediately, buildings are not cheap or easy to turn over, and the impact of such reform would play out over a generation or longer.

Street connectivity is by far the most difficult to fix after initial development. In fact I would say it’s nearly impossible, and is mostly not going to happen. This isn’t because we can’t imagine how to fix the design, it’s because doing so would be a huge investment in low-value, low-productivity places, that is highly unlikely to ever pay for itself. Buildings come and go, but rights of way last forever.

Thus the order of importance: street connectivity > land use diversity > street safety.

Permutations

Using these labels together we can describe different kinds of places in a more nuanced and specific way. I was tempted to try and create a 3x3x3 graphic and attempt to give each permutation a name, but the dimensions don’t really work like that. Instead, a few permutations are common, and most are quite rare.

Most postwar development in the US is single use and not well-connected. Safety varies widely in these places, with newer neighborhood more likely to have sidewalks and some traffic calming, while older neighborhoods and commercial zones are more likely to have wide streets and no sidewalks or safety accommodations at all. These permutations are common:

Disconnected, Single-use, Unsafe

Disconnected, Single-use, Safe for Adults

Sparse, Single-use, Unsafe

Sparse, Single-use, Safe for Adults

Conversely, most pre-war development is at least multi-use, and the streets are usually safe for adults. These permutations are common:

Sparse, multi-use, safe for adults

Sparse, mixed-use, safe for adults

Connected, multi-use, safe for adults

Connected, mixed-use, safe for adults

Applying the terms

Now, it’s tempting to say that the post-war combinations are “suburban” and the pre-war combinations are “urban,” but as we discussed last time that would be missing the point. Describing the functional characteristics of place we care about instead can avoid the baggage and misunderstandings, and will help us have better discussions.

As an example: instead of saying that my parents and my in-laws both live in “suburban” neighborhoods, while I live in an “urban” neighborhood, I could say that my parents’ neighborhood is disconnected and single use, my in-laws neighborhood is sparse and multi-use, and my neighborhood is connected and mixed-use. (They’re all Safe for Adults, so I left that out.)

This is actually pretty helpful, because it describes the qualitative difference between their neighborhoods. I strongly prefer my in-laws neighborhood over that of my parents - the taxonomy highlights the reason.

The other benefit of this system is that is helps us think about how places have changed, or are changing, and the direction they should ideally move. For instance, as a former industrial area, the River North district in Denver was sparse, single use, and unsafe. The area is rapidly filling in with vertical mixed use: residential, retail, and entertainment. Ideally the neighborhood should invest in safer streets, and (if possible) improved street connectivity.

I’ll close by repeating, I hope that these labels could facilitate richer and clearer discussions, especially among people who have taken an interest in cities and how they work. If you made it this far I’m sure you’re one of them, so please let me know what you think! And if you find these helpful in future conversations I’d love to hear about it.

This definition of “developed” is just a rough approximation. I think you can probably trust your intuition on whether a place is generally “developed” or still primarily rural / agricultural / natural.

Wonderful.

I couldn't help but to write down the full permutation grid and assign it a *classification code*.

The code assumes that *Street connectivity* is basically fixed (so, for example, if you live in a D city, you will never turn it into a C city), but the *land use* and *Street safety* allows you (or the city government) to take it to another level. So, for example:

If you start with a D9 city (Disconnected-Single-Unsafe) but you improve the street safety, you can easily turn it to a D8 city (Disconnected-Single-Safe for Adults). However, you're going to need to improve land use in order to take it to D5 (Disconnected-Multi-Safe for Adults) or even D2 (Disconnected-Mixed-Safe for Adults) level. And once you're at D2, it becomes feasible to turn it into D1 (Disconnected-Mixed-Safe for Kids).

Connectivity - Land use - Safety - Classification

Connected - Mixed - Safe K - C1

Connected - Mixed - Safe A - C2

Connected - Mixed - Unsafe - C3

Connected - Multi - Safe K - C4

Connected - Multi - Safe A - C5

Connected - Multi - Unsafe - C6

Connected - Single - Safe K - C7

Connected - Single - Safe A - C8

Connected - Single - Unsafe - C9

Sparse - Mixed - Safe K - S1

Sparse - Mixed - Safe A - S2

Sparse - Mixed - Unsafe - S3

Sparse - Multi - Safe K - S4

Sparse - Multi - Safe A - S5

Sparse - Multi - Unsafe - S6

Sparse - Single - Safe K - S7

Sparse - Single - Safe A - S8

Sparse - Single - Unsafe - S9

Disconnected - Mixed - Safe K - D1

Disconnected - Mixed - Safe A - D2

Disconnected - Mixed - Unsafe - D3

Disconnected - Multi - Safe K - D4

Disconnected - Multi - Safe A - D5

Disconnected - Multi - Unsafe - D6

Disconnected - Single - Safe K - D7

Disconnected - Single - Safe A - D8

Disconnected - Single - Unsafe - D9

Thanks for writing this. We need an urbanist taxonomy.